2029: Retiring Prime Minister Boris Reflects on Triumphant Decade

… but it all hinged on a crucial call early in the little-remembered 2020 epidemic

It is late autumn and we have just caught up with retiring PM Boris Johnson, in expansive – and typically boisterous – mood, having just cut the ribbon on another UK export success story, a nuclear fusion reactor in the depths of a research lab in Oxfordshire. The outgoing PM – now a lean, wiry 66-year-old, a far cry from the tubby blonde of yesteryear – has just completed a decade at the helm and seems to be enjoying a swansong following his latest election victory. Yes: the roaring twenties – the Boris years – a time of social reform, ‘levelling up’, and flourishing of education, the arts, science & engineering, as evidenced by the swarm of visiting dignitaries all over the tokamak fusion device in the machine hall behind us.

The events of recent years do not need retelling, of course – how cake won the day: the ultimately satisfactory Brexit deal that (somehow!) bound Europe closer than ever while also unwinding some of the less savoury parts of EU overreach; rapid developments in technology that raised living standards; and fantastic new cancer therapeutics changing the face of healthcare. And – of course – a rebalanced economy that somehow had managed to rebound after – we must not forget – a very shaky start to the decade, the PM having skilfully steered the nation through the hysteria around the Covid-19 epidemic.

But it could all have been so different. The story is worth retelling, one that the PM himself almost didn’t survive. It was a time of contrast – a glorious spring, yet with a pall hanging over the country; its leader in hospital over Easter with no resurrection in sight.

The key decisions were made the previous month. A fresh-faced PM had won a December election and was riding high in the polls. By his own admission, he was probably enjoying things rather too much, and had taken his eye off the ball:

“there were all sorts of lurid stories of an outbreak of a nasty respiratory disease in China, which then spread to Europe, specifically in northern Italy. We had played it down, the experts had advised on our strategy… but we didn’t take it seriously enough; I didn’t take it seriously enough. But while the outbreak dissipated in China, one export that did infect the rest of Europe was their manner of dealing with it, which didn’t sit well with me: the so-called lockdown, a draconian and authoritarian monstrosity”.

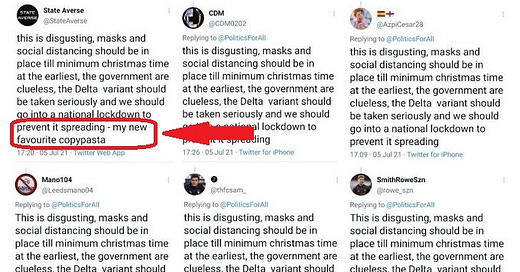

Of course, as we now know, this would never happen in a country such as the United Kingdom – Parliament would not have it, for starters. But the PM is – untypically – pensive: “in truth”, he admits, “it was a damn close-run thing. What we hadn’t reckoned with was social media and the extent to which it had been infiltrated by, how shall I put it, state actors:

“We’re older and wiser now, of course, but at the time the pressure was overwhelming. Throw in former chums like Piers Morgan relentlessly demanding unilateral action, world leaders badgering me to follow their lead and a frenzied press pack spinning every heart-wrenching story the worst possible way, we came very close to the brink. Plans had been made, and I was due to ‘press the button’ on a draconian lockdown on Monday 23 March 2020 – a day that would have gone down in infamy”.

For our classically trained PM, the Ides of March was the turning point. Having played it as cool as possible in an attempt to ‘flatten the sombrero’, some overzealous mathematical modellers from a London university started peddling scare-stories of Megadeaths:

“The pressure became intense. Contingency plans were made, and a working group started working up alternative scenarios. A slightly rabbit-in-the-headlights health minister – I forget his name… Handraab? Wancock? – was getting enthusiastic about what he was calling ‘decisive’ action – the ‘lockdown’ was in play”. As we now know, by that weekend, voluntary physical distancing and hand washing had slowed the spread of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. In northern latitudes we get seasonal viruses that come and go – and after some previously light ‘flu seasons, the initial onslaught was devastating”.

The PM continues:

“What seemed to be the final straw was my call to the nation on the Saturday afternoon to be sensible, keep calm & your distance – perhaps go for a walk. I hadn’t realised that people would follow my instructions to the letter, and – it being a beautifully sunny day after a long winter – everybody did so. The result was pandemonium in the press: ‘lock us down’, they all cried. And I’ll be honest – it almost happened. The speech was written”.

He pauses, before continuing:

“I knew deep down that it was the wrong thing to do, and it felt like there was nothing concrete to go on. But in desperation the previous Friday evening, having announced the closure of swimming pools and other public facilities, I had instructed a young civil servant to work through the weekend and fine me a counter-proposal. The SAGE meeting the previous day had talked of scaring the public into meek compliance, and I wanted to do this differently – there must be another way”.

He grins:

“Or even a third way!”

“Initially, it felt like we were clutching at straws. Despite signs of hope – the Megadeath computer modellers had moderated their forecasts (even they thought the NHS would cope) – but public opinion was in overdrive. The civil servant had managed to bring in an eclectic bunch of scientific luminaries from all disciplines, and a briefing note had been prepared – the key point being that it was not possible for SARS-CoV2 to be simultaneously as contagious as measles and as virulent as Ebola, and – much like it had abated in China, was on the wane in Italy. The rate of increase in infections in the UK had actually slowed considerably. Despite all this, it was inevitable that it was going to be worse than a bad ‘flu season, especially as almost every respiratory mortality was going to be counted as a Covid-19 death. It was a very, very tough call. The temptation to cave in was huge”.

But the PM made the call. The famous oratory from the PM’s speech on Monday 23 March are still spoken of in hushed tones. These were indeed dark times (the death toll rose seemingly inexorably for many days thereafter), but the spark for this most wholesome decade of growth was lit on that night. One of his harshest critics grudgingly admitted that he had managed to channel both Churchill and Attlee in the space of thirty minutes. The message itself was simple: the voluntary measures were working, but the next five or so weeks would be tough. Anyone vulnerable should continue to shield themselves. Keep at it, we’re in this together.

In truth, it was only a stay of execution, but crucial time had been bought to show that the epidemic had peaked, therefore underminding the arguments in favour of draconian measures that of course we know other countries imposed (and subsequently suffering as their economies went into freefall, deaths from other causes spiralled and life chances were truncated). The civil servant and his working group worked feverishly, constructing mechanisms to funnel necessary supplies to those that needed it. Anyone could choose to declare themselves vulnerable and stay at home, and the state paid up. The weather was beautiful that April and we now know that Vitamin D (from sunlight) is critical for mitigating the effects of the virus. But two spirits that can’t be extinguished – those of the entrepreneur and the volunteer – came to the fore. Unlike in other countries where people were locked up in their homes, unable to help those in need, the Great British Public did their bit, though in fact most vulnerable people were actually paid to stay at home. Three new ‘tiers’ of statutory sick pay (medium, high and very high) were introduced for those affected by Covid-19. The amount of money spent seemed obscene at the time, but the UK spent only a fraction of what other countries eventually had to spend to pump-prime their economies.

And yet… even then, things almost came unstuck. Having come under huge pressure to buckle, the PM did indeed succumb to the Covid-19, and as we well know, almost didn’t make it. But the resurrection – or shall we say the raising of Lazarus – on Easter Monday in mid-April cheered the nation. His final words before zoning out into an Easter weekend coma had been reported as “open the schools as planned”, and as he entered a period of recuperation, the Summer term started. Despite terrible stories from the hospitals and tales of heroic deeds in ICU, the spread of the virus continued to slow.

The UK and various other countries such as Sweden (both countries that had had particularly low death rates in the previous winters and so had initially been badly affected) continued the course of voluntary measures, thus limiting the collateral damage and social harm suffered in other countries. In the absence of the highly unsuitable PCR testing used elsewhere later in their outbreaks, at that time both countries were unaware that the SARS-CoV-2 virus had actually reached a ‘community immunity’ level in London by the end of April, and the free mixing of younger, healthier folk meant that this level was also achieved throughout the rest of the country by the end of May.

We now know, of course, that SARS-CoV-2 had been ‘on the loose’ from at least 2018 (and was likely a chimera created by Gain of Function research funded by the NIH, but that is another story). Much of the overall population was never actually susceptible to the virus, and effective treatments were quickly forthcoming by repurposing existing safe therapeutics and prescribing them off-label.

However, the approach worked – community immunity was reached as well as it possibly could have been. And as a glorious summer turned into a soggy autumn of 2020, there was no material uptick in cases, though of course the usual seasonal trends returned – and with the SARS-CoV-2 virus joining the other four coronaviruses in circulation, it continues to feature as a cause of (another) common cold. Vaccines – with all the potential for vaccine escape a la Marek’s Disease – were sensibly only used for the over 60s on a voluntary basis.

Overall, it turns out excess mortality (averaged over time) was flat, allowing the country to continue to invest in healthcare, social care and energy security.

Will the PM’s successor be able to continue the country’s good run? Challenges remain. History tells us that we should never be complacent – a century after that most tumultuous of decades, the 1930s, let us hope that democracy continues to grow from strength to strength.

We must never forget how close we came to throwing it all away. Before bustling away to shake hands with various dignatories, our PM left us with the following words:

“Our children’s futures depend on us holding the line when times get tough and sticking together in the face adversity. God bless the Great British spirit!”

What a story. Hard to imagine now, but one we must remember for evermore.

Subscribe to Alex Starling's Substack

Challenging the Narrative